J.E.L.L.O. (Janky Engine for Lighting & Lattice Oscillation)

CS184 Summer 2025 Final Project Write-Up

Crystal Cheng · Isaiah Tapia · Nandini Velinedi · Walter Cheng

Abstract

Our principal goal was to simulate the soft body physics of jello and its light refraction characteristics. To achieve this, we first constructed a 3D spring-mass lattice incorporating structural, shear, and bend springs, including Verlet integration with gravity to model core physics. The simulation was then stabilized through tuning of spring constants, damping, and time step. To enhance our jello’s visual realism, we implemented a custom translucent shading model with specular highlights to produce the shiny, gelatinous appearance of real jello. Finally, we incorporated all these elements into a complete simulation scene featuring a plate that our jello rests upon, and a background with lighting, capturing all frames through the OpenGL viewport. An interactive component allows users to click and drag around the jello on the plate, resulting in dynamic jiggles that respond naturally to the applied forces. Our end result is a realistic-looking, visually satisfying, interactive jello simulation that accurately showcases soft body dynamics with appealing rendering.

Technical Approach

We implemented a spring–mass lattice for deformable-body dynamics, integrated via position-based Verlet for stability, and rendered with a lightweight translucency model inspired by BSSRDF effects but optimized for single-pass real-time shading.

Core Physics

Our soft body dynamics are modeled using a 3D spring-mass lattice system inspired by the 2D approaches for physically based simulation also used in Homework 4. The structure lended itself to a similar implementation as was seen in Homework 4, however given the 3D dimensional nature of our simulation we were met with unique problems and workarounds that we otherwise would not have needed to account for in Homework 4.

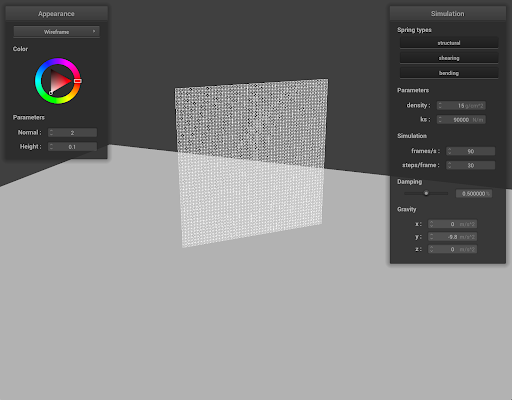

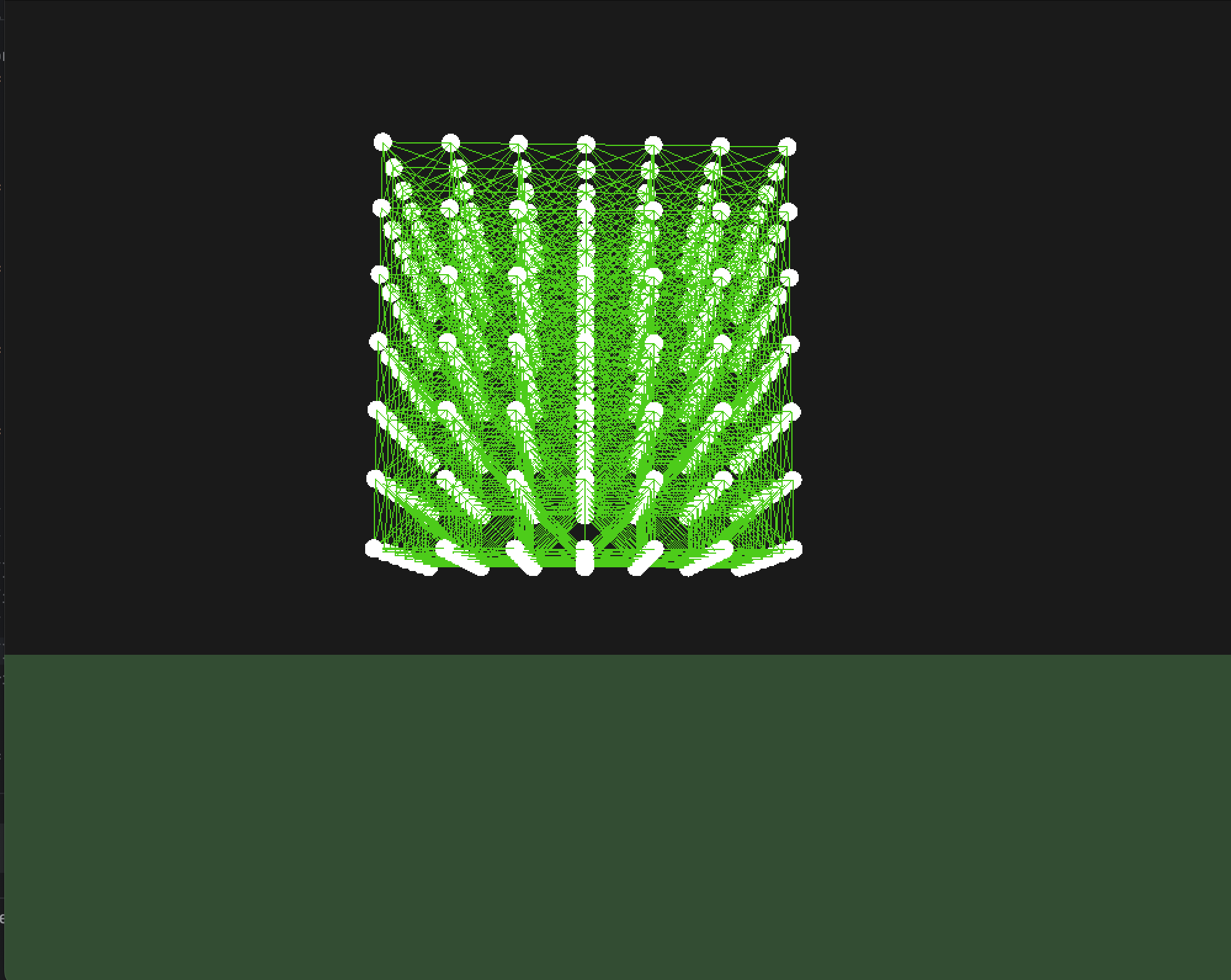

The lattice consists of three types of springs connecting point masses in a cubic configuration to approximate the elastic behavior of jello: structural, shear, and bend. We integrated motion using Verlet integration since it offers numerical stability and is fitting for real-time interactive applications like our jello model.

The core class Cage manages the state and physics of the mass-spring system. Each point mass stores current and previous positions, accumulated forces, and mass; we use Verlet integration for stable time-stepping where positions are updated without explicitly tracking velocities. Constraints such as floor collision and spring length limits are added to prevent unrealistic deformations and maintain physical plausibility.

Simulation

After implementing the core physics structure, we tuned spring constants, damping, and time step for physical stability. We found that the body retained its structure best when our springs rigidity increased with the number of point masses we added, i.e. damping ought to be relative to the mass being exerted from more point masses. Simulation stability and realism depend heavily on our parameters. Forces on springs are computed using spring constants rigidity (k) and damping (kd).

At each time step we update the physics of our system. Applying gravity to all of our point masses afterwards we iterate over all springs to determine what our spring forces should be, we then update the corresponding point masses accordingly. Each force is computed as the damping coefficient times the normalized force direction multiplied its magnitude.

Verlet integration computes the next position by iterating over all point masses, computing the acceleration (a) and the vector from the previous point to the point mass's current position. We had initially used the form recommended by the homework, Verlet update: \[ \mathbf{x}_{t+\Delta t} = \mathbf{x}_t + (1-\gamma)(\mathbf{x}_t - \mathbf{x}_{t-\Delta t}) + \Delta t^2\,\mathbf{a}_t \]. But we found that using its simpler form worked a bit better, reducing our instability \[x_{t+dt} = 2x_t - x_{t-dt} + a_t \cdot dt^2\].

Visual Rendering

After our model was set, we wanted to enhance the visual realism of our jello object by implementing a fake translucent shading model with specular highlights to achieve a shiny gelatin-looking surface. We used a two-stage GLSL shader setup:

- Vertex Shader (translucent.vert) - To transform vertex positions and normals into world space and compute lighting vectors such as light direction, view direction, and the halfway vector, we implemented this vertex shader that then passes these values into the fragment shader.

- Fragment Shader (translucent.frag) - We experimented with a hybrid Blinn-Phong shading model for the base diffuse and specular lighting. An added angle-based translucency term helped fake the backlighting effect that we often see in real life gelatin objects.

Rendering Notes (Translucency & Specular)

For the Blinn-Phong shading, we used a diffuse term of \[ \mathrm{diff} = \max(\mathbf{n} \cdot \mathbf{l}, 0) \], where n is the surface normal and l is the normalized light direction. Similarly we used a specular term of \[ \mathrm{spec} = \max(\mathbf{n} \cdot \mathbf{h}, 0)^{32} \], where h is the halfway vector between light and view directions and the exponent of 32 represented the shininess needed to achieve a glossy jello look.

Instead of implementing full subsurface scattering, we used a lightweight approximation that doesn’t require multiple samples nor a scattering profile of \[ \mathrm{backLit} = \max(0, -\mathbf{n} \cdot \mathbf{l}) \]. This measures how much the surface is facing away from the light. Next, the translucency is linearly interpolated as \[ \alpha = mix(0.3, 0.8, \mathrm{backLit}) \]. A higher alpha when backlit creates the illusion of light penetrating our surface and glowing through thinner areas.

Although this visual look was inspired by shading models for BSSRDF-based subsurface scattering, we changed it to a simplified form suitable for real-time rendering. Our version is a single-pass approximation per fragment and doesn’t require additional render targets or deep shadow maps. We also modified the Blinn-Phong model, which is opaque, to include a custom alpha formula based on lighting geometry to mimic translucency.

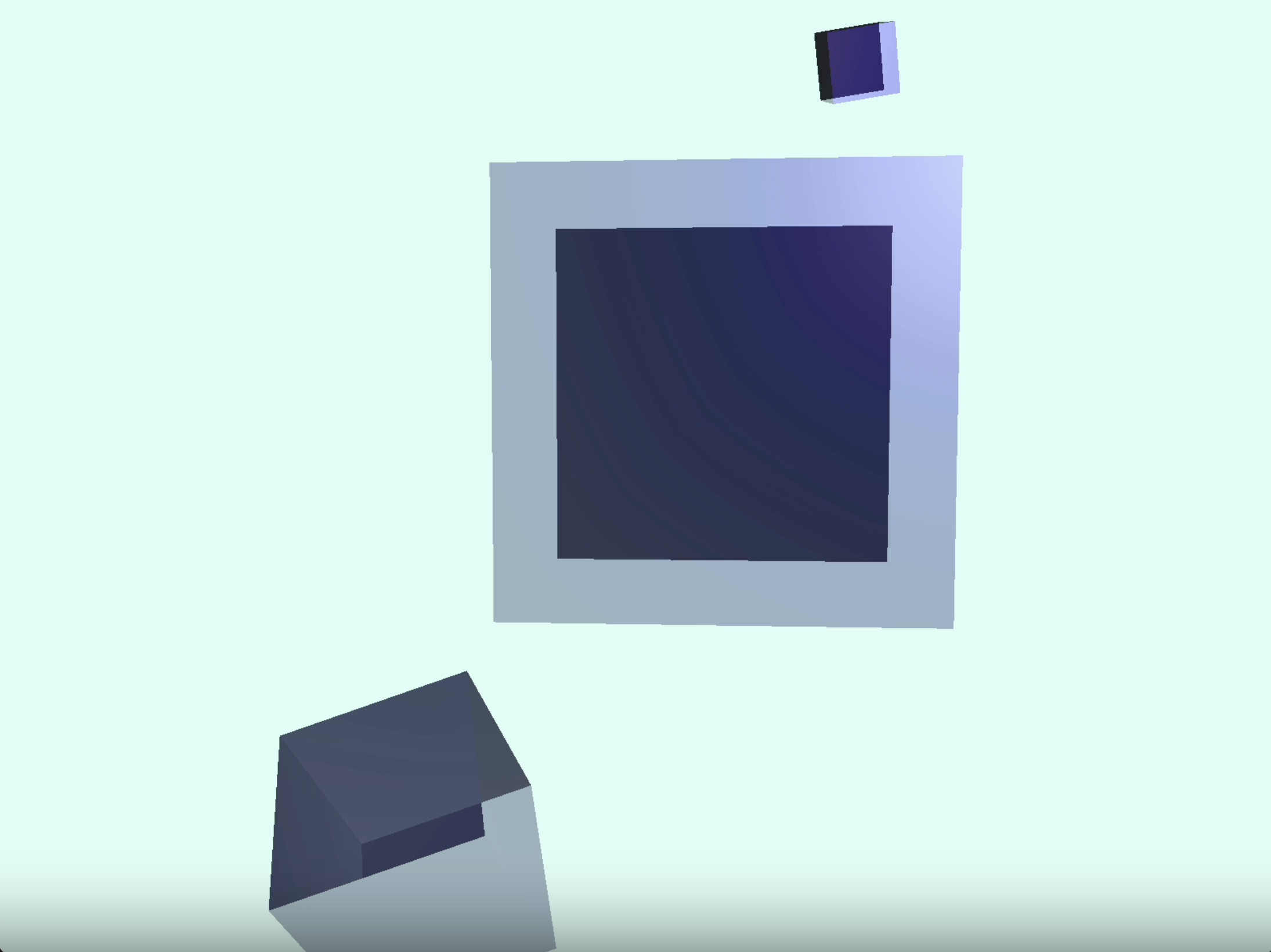

Scene

Lastly, building off the visual rendering, we set up a simulation scene where the translucent red jello cube can move around a

Cornell Box with red, blue, and green walls. We modelled our jello object using Blender tutorials and exported it as an object into our folder. We then

load in our jello model with a direct pathway to the object:string modelPath = "resources/objects/jello/jello.obj";.

These simulation frames are all captured using the OpenGL viewport. An interactive component allows the user to use arrow keys to

move the jello, producing dynamic jiggles that respond naturally to applied forces.

Problems

Our idea initially was to finish working on HW 4 and try to build on the 2D structure that was given and make it a 3D structure which was super difficult. We spent a whole day trying to figure out how to implement this change, but we later came to realize that debugging our code was a big waste of time, and that is when we decided to extend the functionality to OpenGL.

During the shift we encountered (incredibly annoying) issues transferring code from Windows to macOS because of GL loader differences, IDE file structure traversal ,path case-sensitivity, trackpad input deltas, and deprecated libraries on different OS. We resolved these by unifying our build with CMake presets, switching to a cross-platform GL loader, and normalizing input scaling.

Learn

Homework 4 helped us a lot in applying what we learned in class. It was the foundation of our project as it taught us how to work with masses, springs, forces, Verlet integration and shaders. We also learned a lot about the physics behind the soft-body simulation and how to implement it all in OpenGL. Having the creative freedom on this project allowed us to think outside of the box and although it was frustrating at times, it was all worth it!

One thing each of us learned from this project: Isaiah was introduced to physics and how to implement it on a soft-body, Crystal learned more about shaders and translucency and got to play around with the colors of our jello, Walter learned about the stability of meshes and instability of simulation and had a fun time playing around with that, Nandini learned more about working with masses and springs and enjoyed implementing the physics behind it.

Results

Our final result is a jello cube able to be moved around by the up, down, left, and right arrow keys. Pressing the space key moves the jello upwards, allowing it to fall down and produce soft body jiggle physics.

References

- Solaro — Gelatin Cubes: Soft Body Simulation

- CMU — Jello Cube Simulation/Animation (slides)

- Physics of JellyCar: Soft Body Physics Explained (YouTube)

- GPU Gems — Real-Time Approximations to Subsurface Scattering

- Jello, World! (Spring 2023 Final Project)

- CS184 Spring 2025 — Homework 4

- OpenGL Tutorial — Model Loading

Contributions from Each Team Member

| Team Member | Contributions |

|---|---|

| Crystal Cheng | Crystal worked on shaders and our initial idea of importing a mesh and having the vertices correspond to where they appear on the mesh. She debugged CMake and OpenGL issues to ensure the project was built consistently on all teammates’ devices across Windows and MacOS. For rendering, she implemented the GLSL shading pipeline and Blinn-Phong lighting with an approximation of subsurface scattering. She also largely worked on the write-up report and slides. |

| Isaiah Tapia | Isaiah worked on the initial spring and point mass structure. Borrowing from Homework 4, he helped to extend the functionality of the mass spring system into the 3D world space as well as the position for each time step. Isaiah also worked on the interactability portion of the project. Specifically on the world cube jello user interface and the necessary physics to implement it. |

| Nandini Velinedi | Nandini worked on implementing HW 4 which included working on the masses and springs to build a 2D mesh grid which was the base of our project. Also worked on implementing the Verlet integration on the grid to apply forces on the masses to make them move. Tried to build a 3D lattice based on HW 4 structure but failed so had to move to the OpenGL to make it work. Helped set up the slides! |

| Walter Cheng | Set up OpenGL engine using the LearnOpenGL tutorials to get a 3d scene with a movable camera, basic shaders, and .obj model loading. Constructed cage.h with custom point mass and spring shaders, extended to Cube class and wrote the lattice construction algorithm. Implemented object and cage view toggling and simulation play/pause. Helped debug/develop Verlet integration and spring force calculation, friction physics, and constraints. Created algorithm to fill model with lattice structure. |